Writing and Media by Christopher Trotchie

When the Native Americans from Standing Rock Sioux Reservation called for support, tens of thousands answered by standing on the front lines or donating materials. Much of this help comes from the Pacific Northwest, Eugene and even the University of Oregon.

When an Emerald reporter arrived at camp, he found the largest demonstration of Native American unity in U.S. history.

Arrival

The inside of an 18-by-36-foot Army surplus tent is pitch black when the lights are off. The walls and ceiling are made from a thick, rubberized canvas that blocks any light from the outside. Even with a cast iron woodstove in the corner — the kind you might find in a cabin — the inside of the giant green tent is cold. It’s around 10 degrees outside — and that’s warm for a North Dakota winter.

The silence is broken by the sound of someone walking in the distance. With each step, the sound of snow and ice crunching underfoot grows louder until it stops outside the doorway, then comes the sound of a gas cap being twisted off the generator outside, and with two heaves on the pull cord, an engine coughs to life. The dingy, overhead light illuminates a room full of bunks.

No one stirs when the light comes on, but trying to go back to sleep is a waste of time. It’s around 8 a.m. and there is much to do every day in Oceti Sakowin camp — the last obstacle for Dakota Access Pipeline’s $3.8 billion project. A community meeting at “the dome” starts in an hour and, time for coffee included, that’ll already be a hurried walk.

Outside the tent, the sound of helicopter blades thumping against the air drowns out the buzz of the generator along with any semblance of tranquility. The thundering bright yellow chopper reminds protestors this is no camping trip — it’s an occupation of federal land.

It might take years to unpack the myriad of complexities posed by the one-year Standing Rock protest. It was the biggest clash between American Indians and the federal government since the Wounded Knee incident in 1973, when Native American activists seized a small town in South Dakota to protest tribal corruption and treaty rights.

Over three decades have passed since that confrontation, but relations between Native Americans and the U.S. government remain strained.

Despite the historic efforts of Native American tribes and their allies, the protest at Standing Rock began to take its final breath as the inclimate weather moved to the great plains.

After harsh winter conditions arrived in North Dakota, the dangers facing the protesters became a liability for the tribe. The tribal council of Standing Rock pulled its economic and infrastructural support — the protest was taking important resources away from the reservation.

The council decided to pursue a continued fight through the court system, attempting to have the Army Corps of Engineers complete a promised environmental impact statement. In the end, the Trump administration rescinded a halt on the project put in place by President Barack Obama.

On Feb. 23, Oceti Sakowin was cleared of protesters by local law enforcement.

The pipeline is now complete.

The following stories are meant to provide a better understanding of the events that have taken place at Standing Rock over the last year and the role Eugene residents have taken in them.

<It Became Real to Me

When University of Oregon professor Torsten Kjellstrand stood at the top of Facebook Hill in Oceti Sakowin camp, he was struck by the beauty. The camp was spread out into the distance, and the setting sun bathed the tents, teepees and RVs in golden light.

“I had been following the news rather closely. And my impression was that it was a very small place,” he said. “And when I got there, I mean, it's a great American plain.”

Looking over the camps and open range through the viewfinder of his camera, Kjellstrand realized that the protest was more than just a fight over a pipeline. There was history here.

“It became real to me that people had been living here for thousands of years in places like this,” he said.

Kjellstrand, born in Sweden, is a professor of practice at UO, teaching photojournalism, multimedia and visual journalism. Much of his photography centers around the stories of underrepresented peoples.

For the last few decades, Kjellstrand’s work has focused on documenting indigenous communities around the Pacific Northwest. He prefers to work on series because it gives him time to develop relationships and a solid understanding of the community, something he thinks is particularly valuable working with underrepresented groups.

Being an immigrant himself, Kjellstrand identifies with how it feels to be on the outside looking in.

“We come in with an idea that this is how Indians are supposed to be, and then that's what we find and we photograph … instead of being open to the idea that we may not know.”

Kjellstrand thinks there is a lack of respect in the U.S. for the sovereignty of Native American nations, which plays into conflicts like what has occurred at Standing Rock.

“We think that reservation land is stuff we've handed to them. That simply isn't how it happened. There were people living here and Europeans came through and just kind of set up house, set up shop on this land,” he said.

What originally brought Kjellstrand to the rustic plains was a project he is working on to document indigenous people. He sees it as an effort to preserve this time and place for future generations of Native Americans.

One practice the photojournalist brings to his project is that he prefers to not use the term “Native American” as he compares it to calling all people from Europe “European.”

“I try to call people by their tribal affiliation. It's very hard to do it because people come from all over,” he said. “I'm a European, but I don't really identify as a European — I identify as a Swede, which is different than being an Italian.”

Kjellstrand’s trip to Standing Rock began as an opportunity to witness a cultural phenomenon that may not take place again in his lifetime. One of his biggest concerns was not having enough time to take the photos he wanted to.

But after being at Standing Rock, he was more focused on the positive impact the Water Protectors may have on the larger issue of Native American sovereignty.

“I hope that what's happening in Standing Rock will make us more receptive to the idea of listening to the people who have been here all along,” he said. “That's my hope.”

The Seed to Kill the Snake

In the nation of the Sioux there are multiple warrior societies. The Aki’cita are one of the proudest.

The word Aki’cita seems as old as the hills of North Dakota. It means tribal police, or guard unit. Historically the Aki’cita were responsible for organizing the annual buffalo hunt and refining their art of war. Edward P. Blackcloud Sr., born on the Standing Rock reservation, is one of a new generation of these protectors. He has lived on the reservation most of his life, and when the tribal council made the decision to pull its support of the camps, he was there. With each word the council spoke, Blackcloud could tell the door was closing on a resistance he was completely vested in.

When it was his turn to speak, Blackcloud rose from his chair and took the 10 steps to the microphone. His voice broke with emotion as he addressed the council. He asked, how could they do this? He wanted to know what would happen to the people in the camps who had no place to go. He wanted to know how, after asking people to come stand with them, they could turn their backs?

“A lot of the individuals have given their hearts and stuff to this movement. And now they’re being asked to go home. And some of these people have no homes to go to because they sold them. And that’s what hurts me,” he said during an interview after the meeting.

The drive from Fort Yates, where the meeting was held, back to Blackcloud’s hotel was somber. Blackcloud sat in the passenger seat of a late ‘90s all-wheel-drive Astro van whisking along two-lane Highway 1806.

After arriving at the hotel and settling into the room, Blackcloud acknowledged the positive impact the movement is having, despite its imminent end.

“Standing Rock planted a seed. And that seed was to kill the black snake of the world — which is killing Mother Earth. And that seed has grown throughout the world, and I think we’ve done a lot of good by standing up and showing the world how to continue the struggle.”

The event that stands out the most to Blackcloud was a summer day when clergymen came to the backwater bridge to protest the multi-billion dollar project.

Blackcloud stood inbetween the clergymen and DAPL, ensuring they would not be harmed during the ceremony they held on the bridge that day.

“To me, I felt like that was the meshing of the religions ... To me, that was one of our most powerful moves right there,” he said. “When the clergymen of the world united with us that day. That meant thousands and thousands of people were uniting with us.”

As the protest went on, Blackcloud began to notice a shift in the ethos of the camp and the quasi leadership. For him, the hardest part about living in the camps became dealing with a division amongst the people. The fabric of their cause was deteriorating without solid leadership.

“Everybody wants to be a chief and no Indians ... And then it kind of went off track a little bit.”

Build it. Get’er Done.

Thomas Donald Nudd is a township supervisor in the city of Harvey, North Dakota, about 160 miles northeast of Standing Rock Reservation. He disapproves of the protest taking place in his state and is frustrated about a mounting bill for taxpayers.

Nudd said he isn’t mad that they are protesting but that the situation escalated to this point. He believes the Native Americans of Standing Rock had plenty of opportunities to negotiate a deal. He says that because they didn't use the system to their advantage when they had the chance, none of this should be a surprise.

“Am I sympathetic to the Native Americans? Yes. But not over this,” he said. “They have been given some raw deals. This is not a raw deal. And very few of the Indians that are alive today probably get raw deals. Their forebearers got the raw deals.”

Nudd draws from his own experience when talking about the conflict over the use of easements. He remembers a time when the utility company came to him about building on his ranch. He didn’t want their project crossing his land because it would inconvenience the way he grows hay to feed his cattle.

The placement of a large power pole, had the project gone through, would have made it impossible for him to drive his tractor over sections of his fields.

Nudd went to the community meetings he could and talked with other community members affected by the potential project. During that time, he found that a neighboring landowner had the ability to have the project cross his land without it causing an issue. In the end, Nudd believes that his persistence to find an amicable solution is proof that when it comes to the dispute happening between DAPL and the Sioux Indians, they could have worked something out.

When it comes to how Nudd feels about the out-of-state protesters, he does not mince words. One of his major concerns is that all of the people who are coming from out of state are going to leave when this is all over. He thinks that the mess that is being created will be left for the state to deal with.

“I don’t think any protesters coming from outside the area belong here,” said Nudd. “If you’re not directly affected, then you shouldn’t be here.”

Nudd is also concerned about the burden the protest is having on the court system in North Dakota. With over 600 arrests made at protest locations, the cost is only growing. Providing attorneys to out-of-state protesters is costly and adding to the multi-million dollar bill the state of North Dakota is racking up.

“Why should we pay for their legal defense? These protestors that were in court weren’t in court because they were protesting. They were in court because they broke the law.”

For Nudd and many who live in North Dakota, the protest is affecting them more directly than others around the country. Their tax dollars are paying for increased police presence and court officials. Although he says he sees the reasoning for the protest, he does not believe in the cause. He is ready to move on, finish the project and “get’er done.”

“If they want to protest, I don’t have a problem with that. Let’s not break the laws. And let’s have the protests over an issue. All of a sudden every time somebody gets a microphone in front of them, they want to talk about something besides the pipeline. They want to talk about what happened a hundred years ago.”

Here to Serve

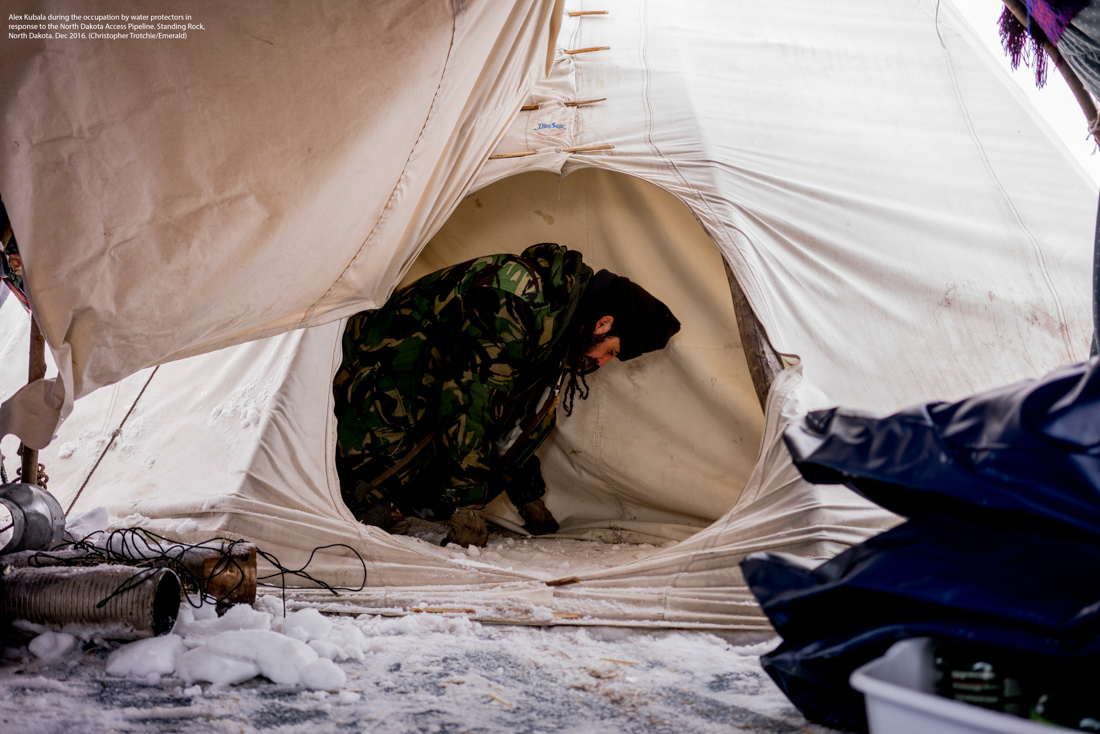

Alex Kubala answered the call for solidarity at Standing Rock from Wisconsin. The 35-year-old traveled 800 miles with three teepees on the roof of his van and back seats full of supplies — packing for an indefinite stay.

Kubala never saw himself facing down the federal government over the sovereignty of Native Americans. He never thought his face would be ground into the pavement, but he came to serve.

For Kubala, it was an opportunity to be a part of something he described as bigger than stopping a pipeline. The opportunity to support the sovereignty of the Sioux justified uprooting his life and moving to live in the camp.

His pledge to support sovereignty was put to the test the day the tribal council pulled support of the camps.

“I came here not to have my own agenda, but to support the tribe. Support the people. It’s about tribal sovereignty and honoring that. So if the tribe [says] it’s time for you to go and they’re wrong, I still have to allow for them to make the wrong decisions. That’s what tribal sovereignty is. I don’t get to decide. I’m here to serve.”

Kubala has been part of the camp since June 2016. During his time there, he has seen just about everything the camp has to offer. One of the more memorable parts of camp life might be the change he has seen in people during their time there.

“I’ve seen so many people transform their lives, their hearts. They’re devoted now ... all these people that are like ‘I’m never going to be able to go back to my normal life.’ It’s a huge success. We’ve deeply transformed thousands of lives, if not more.”

Kubala is resolute that the actions in Standing Rock will have lasting impacts on the general public. He sees the awareness the movement created as the real victory.

“Just because we're moving out of the floodplain doesn’t mean we’ve lost. This fire needs to be nurtured and carried ... The opponent we’re up against — it’s not any small thing,” he said. “I hope we go from here remembering the strength of what we’ve done — that we remember the power of coming together in prayer and we continue to inspire the world to keep that fire burning. To keep standing up. And to carry that fire everywhere we go.”

A Privileged Decision

Levi Gittleman is third-year Journalism student at the University of Oregon. When the opportunity to travel to Standing Rock became possible in September 2016, he jumped. He had the money, a break in his schedule and a passion to see what was happening in North Dakota.

With a bit of coaching from instructors at school and support from his parents, Gittleman booked a ticket and was standing in front of the airport in Bismarck, North Dakota, just two weeks later.

While waiting for his cab, Gittleman recognized a photojournalist named Tom Jefferson smoking a cigarette. Jefferson is well known for his work documenting the events at Standing Rock. Gittleman introduced himself and the two quickly became friends.

Jefferson invited Gittleman to take a bus rather than allowing the student to pay $100 for a taxi to the camp. Their relationship afforded Gittleman an opportunity to see a side of the camp that he might not have seen otherwise.

“We’d go to those and dance and sing and pray and have as jolly of a time as you can ... I try to refrain from making it seem like too much of a good time at night, but it was honestly fun to see all these beautiful people dancing and singing and praying together in unison. It was a really moving, beautiful experience.”

During the four days Gittleman spent in the camp, he became familiar with a culture foreign to him before the trip. The impact it had on Gittleman is something he is still processing, and he says it might be a long time before he understands completely how deep those effects have gone.

“I prayed more than I’ve ever prayed. I meditated more than I ever meditated before. It was a very spiritual thing to go there,” he said.

One major realization struck Gittleman after he returned to Eugene.

While talking to a group of classmates about his experience, one of his peers challenged his motivation for the trip. He pointed out that one reason he was able to go to North Dakota was because of his privilege. Gittleman said those words stung, but as he mulled it over, the sting was replaced with frustration.

“Partly, [my trip] signified this “white man” who had the money to go over to North Dakota and protest and use it for his own personal benefit to have a story and to experience this idea of culture and protest. It was almost a selfish decision to go there, just because I could.”

For Gittleman, the trip was life changing — but not for the same reasons as when he left.

“There’s no need to go travel somewhere to support when I could do just as much supporting on social media or activism in my own community.”

The View from the Longhouse

Anna Hoffer still feels the chill of the North Dakota winter sometimes.

Hoffer is a co-director of the Native American Student Union at the University of Oregon. They said that even though they are over 1,000 miles away from Standing Rock, they are very much connected to what is happening there.

Hoffer said that they felt accepted at the camp in a way they weren’t accustomed to.

“First and foremost, I was a human. It was really beautiful to not have to feel scared to walk through [camp], or have to think about my position in the world. It mattered, but it was different. It was also the first time that I, as a Native person, felt respected,” they said. ”People listened to me as a native person. Whereas being out here, it’s iffy because I’m a ‘light skinned.’ ”

Hoffer was arrested in North Dakota while participating in a prayer circle at a shopping mall in Bismarck. They and a friend stopped to put a Water Protector patch on the back of their friend’s jacket when a police officer approached them wearing full body armor, holding an assault rifle.

“They were geared up for a war.”

Being Native American at the University of Oregon can be lonely, Hoffer says. Without NASU or the Longhouse, they aren’t sure they would feel comfortable enough to stay on campus.

When Hoffer talks to other students about Standing Rock, they get the feeling that most people took it off of their priority list when former President Barack Obama directed the Army Corps to not issue the easement for drilling to continue.

They want people to be aware that there are projects like the DAPL project all over the world.

“This is something that has been building up for a long time. We are getting tired of the fact that treaties keep getting broken, that we keep getting mistreated. No one pays attention to those things. People still don’t know.”

For Hoffer, there is a lot of frustration surrounding what has happened at Standing Rock, but their resolve to keep fighting is unwavering.

“We are not going to stop fighting. We will always be there. And if it is not Standing Rock, it will be something else. Natives are not going to be silent any more.”

Q&A with David Archambault II, Chairman of Standing Rock Reservation

December 2016 - Leading up to the Dissolution of the Camp

Emerald: What is the best way for people in Eugene to help?

Dave Archambault II: I get that question asked all the time, “What can I do?” and I don’t think there is one answer. Whenever they come and they ask, there is so much that can be done. ... What we try to do is just put the information on what the tribe is doing because there's so many different interest groups, and we have a website called Standwithstandingrock.net. And if it's something like divest from banks that are funding this, or if it's writing a letter to Congress, or writing a letter to the administration, or writing requests or asks to the company or whoever, we have some templates on there. When it comes to donations ⎼ the tribe didn't ask for funds ⎼ but people want to give to the tribe, and we're thankful for that. So we have a tab on the website where you can donate on there, or if you want to give to whoever, there's 5,500 different GoFundMe accounts. You could fund whatever you want. What I tell people is, it's up to you whatever you want to do; follow your heart. And that usually takes you in that direction that you need to go.

E: What do you think the general condition of the camp is right now?

DA: Well I haven't gone down there lately, because when the first storm came, I asked everybody to leave. And the second I made that statement somebody else from Standing Rock made the statement “don't leave.” And then there's been a lot of criticism on me saying that I sold out, and that I have a house in Florida, and that I have another house in Bismarck, and that I received money. And none of that's true, but it's just how everybody has turned on me. So it makes me curious about [what people's intention are]. What are they here for? When we had the decision made by the Corps of Engineers not to give an easement, and to do an [Environmental Impact Statement] and to consider rerouting ⎼ those were the three things that we've been asking for the last two years. ... So the purpose of the camp was fulfilled, and we got what we wanted. I understand that it's not over. This new administration can flip it, so what we're doing now is trying to do everything we can to make sure that that decision stays, but even then it's not guaranteed. Right now it's dangerous ⎼ tomorrow we're going to get 15 inches of snow, 55 mile an hour wind. It's not safe at the camp. And from what people are telling me, there's a lot of empty tents all over and a lot of trash, and if we don't clean up, when the flood waters rise all that stuff is going to be in the river. So we're going to, at some time, get down there and clean up.

E: What is the biggest misconception about you currently?

DA: Just the perception that I'm not here for the fight is false and it's wrong, and that's kind of disturbing to hear all the fabricated lies about me when people don't know me. People really don't know who I am. And when somebody says something, and it's believed and it's passed on, it's sad because we we're the ones who started this whole thing. This tribe is the one who stepped up and filed the suit when we knew that we didn't have a chance. We knew that the federal laws that are in place are stacked against us. They're in favor of projects like [the pipeline], but we had to do it.

E: What is the impact of the protest on the tribe as a whole?

DA: On Standing Rock, we have eight districts. We have 12 communities. We have highways. We have our schools. We have ambulance services. And now because people choose to stay at the camp, we have to make sure that they’re out of harm's way. So when the storms happen, we're going to have a shelter here in Cannon Ball, and people are going to come. And they're going to expect food, and they’re going to expect heat, and they’re going to expect blankets. So we provide that because it’s an emergency shelter. And then when the danger is gone, they stay there. They don't leave. And the community says, “We want our gymnasium back.” ... There's really nothing going on. There's no drilling going on. But they want to be there, and I think it's because there was a good feeling when it first started. When we came together, tribal nations came together, and we prayed together, and we shared our songs, we shared our ceremonies. And it was a good strong feeling, but nobody wants to let that go. Nobody wants to move on. Those things that we learned from that lesson are things that we can take home to our communities and apply. We come from communities that are dysfunctional. We fight our own family, we fight each other's families in the community, but what happened here was we were able to live without violence and without drugs or alcohol, without weapons. And we were able to do it with prayer and coming together. That lesson right there is something that we need to take back to our communities, but we don’t want to now. There are people down there that don’t want to leave. They think it is the greatest thing. But when you ask me ‘what's the status,’ the things that I hear if I go down there, I don't hear the good things anymore. I hear ‘this person did this,’ ‘they took this,’ and now I'm getting accused of doing that. So what we're doing is bringing that dysfunction into something that was beautiful, and we're letting the lessons slip through our hands. And we're not learning. We're hanging on to something that's not there anymore. And so, I know that there's a chance that this pipeline has to go through, but it's not the end. It's not the end of everything. We have to take the things that we learned, and accept it as a win. We have to take the processes, the policies, the regulations, the rules that are going to change because of what happened here, and take it as a win. Whether that pipeline goes through or not, I think we won.

E: How do you feel about the example that Standing Rock has set for other land struggles in the United States?

DA: This isn’t the first pipeline that anyone's stood up to. This isn’t the first infrastructure project anyone’s stood up to, and I don’t think it is going to be the last. But it is something that we have to be mindful about though: if we're going to take on the oil industry, it’s not going to be at the pipelines. We have to change our behavior, and we have to demand alternatives, and we have to start doing things different, and we have to stop depending on the government. This country is so dependent on oil. The whole nation is dependent on oil. If we want to fight these things, it's not going to be where it's being transported. It's going to be at the source, and it's going to be with the government.

E: Who is responsible for the camps?

DA: There's never been anybody that was responsible. It was forever evolving from day one. The way it started was there were kids who said, ‘We don't want this pipeline to go here.’ We don't want oil in our water. So they ran from Wakpala to Mobridge over the Missouri River. They did it with prayer. Then the second thing that happened was a group of people got together in April and said we need to set up a spirit camp. So the first spirit camp was set up with prayer and then there was a ceremony, and in the ceremony individuals were identified to help with this. So when we had our first meeting, [there were] 200 people from Pine Ridge and 300 from Cheyenne River coming the next day. Where are they going to go? Where the spirit camp was set up was already bursting at the seams. ... I brought the different groups together and I said, “We need to coordinate. We need to know what each other are doing.” Then they said I was colonizing them, and that I was trying to control them, trying to dictate to them because I was IRA government. It seemed like every time the Standing Rock Sioux tribe tried to help, we got bit. So you ask me who is running the camp down there? It’s whoever the people want to listen to and there is always someone who doesn't want to listen. That is the disfunction. The good thing about the tribal government is [even] if the people don't want to listen to me, it’s a role that everyone accepts. Down there, if someone does not accept it, [the leadership] will change. That is how it has been going. It’s been forever evolving from the first time we set up until today. Even now if I go down there, they’re not going to want to have anything to do with me because I asked them to leave.

E: Do you genuinely want people to leave the camps?

DA: Yeah. There is no purpose for it. What's the purpose?

E: There seems to be some concerns for safety in the camps; how should these concerns be addressed?

DA: I don't want that pipeline to go through. I just don’t want anyone to get hurt, I don’t want anyone to die, I don't want any kids to get abused, I don’t want any elders to get abused, I don’t want any rapes to happen. They don’t want any authority down there. What do you do then? Do I have to close it down with force?

E: I don't know... Do you?

DA: No, I'm not going to do that.

E: Why not?

DA: I don't want that. I don't want Wounded Knee. I don’t want to fight my own people.

I tell you what, when I say stuff and when I do stuff, it feels like no one is behind me. And I feel like I’m the only one that thinks like this. I feel like I’m the only one that really understands, and it makes me question whether or not I’m Indian.

Am I Indian enough? How come I don’t want to be there? And how come I don’t want to put people’s lives on the line? How come I don’t want to think it’s okay for them to die? I must not be Indian. I must not be Indian enough.

What I saw happen was something that was beautiful. Then I saw it just turn to where it’s ugly, where people are fabricating lies and doing whatever they can, and they’re driven by the wrong thing. What purpose does it have to have this camp down there? There are donations coming, so the purpose is the very same purpose for this pipeline; it’s money. The things that we learn from this camp — the things that were good, that people are doing whatever they can to hold onto — are slipping through their hands at this moment. And I feel like no matter what I say or what I do now, because it flipped and it turned, I have to be really careful; because they will say that I'm trying to facilitate this pipeline. That’s the last thing that I want and I’ve always said that. ... We were offered money; I don’t want money. We were offered that land; I don’t want that land. I don't want anything. I just don’t want that pipeline. It’s symbolic if I can stay with that course. We are so close, but there is a chance that it could go through. If it goes through, I’ll be the worst chairman ever, and if doesn’t go through, I’m the worst chairman ever. So there is no win for me. I don’t want a win; I don’t want anything from this. What I see is something that is so symbolic it could change… We have a chance to change the outcome for once: the outcome of who we are as people. There is a real opportunity here, and that is what I want. That is what I'm hoping for, is that we take these lessons that we are learning and change the outcome of who we are and what we are about and the future of our people.

Coder - Peri Langlois

Art Director - Dana Sparks

Photo Editor - Adam Eberhardt

Podcast Editor - Franziska Monahan

Contr. Design - Nicole Petroccione

Contr. Video - Kylie Davis

Editors - Cooper Green, Braedon Kwiecien

Special Thanks - Rowena Jackson, John Sanchez